The species problem

It is difficult to define a species in a way that applies to all organisms. The debate about species delimitation is called the species problem. The problem was recognized even in 1859, when Darwin wrote in On the Origin of Species:

No one definition has satisfied all naturalists; yet every naturalist knows vaguely what he means when he speaks of a species. Generally the term includes the unknown element of a distinct act of creation.

When Mayr's concept breaks downedit

A simple textbook definition, following Mayr's concept, works well for most multi-celled organisms, but breaks down in several situations:

- When organisms reproduce asexually, as in single-celled organisms such as bacteria and other prokaryotes, and parthenogenetic or apomictic multi-celled organisms. The term quasispecies is sometimes used for rapidly mutating entities like viruses.

- When scientists do not know whether two morphologically similar groups of organisms are capable of interbreeding; this is the case with all extinct life-forms in palaeontology, as breeding experiments are not possible.

- When hybridisation permits substantial gene flow between species.

- In ring species, when members of adjacent populations in a widely continuous distribution range interbreed successfully but members of more distant populations do not.

Species identification is made difficult by discordance between molecular and morphological investigations; these can be categorized as two types: (i) one morphology, multiple lineages (e.g. morphological convergence, cryptic species) and (ii) one lineage, multiple morphologies (e.g. phenotypic plasticity, multiple life-cycle stages). In addition, horizontal gene transfer (HGT) makes it difficult to define a species. All species definitions assume that an organism acquires its genes from one or two parents very like the "daughter" organism, but that is not what happens in HGT. There is strong evidence of HGT between very dissimilar groups of prokaryotes, and at least occasionally between dissimilar groups of eukaryotes, including some crustaceans and echinoderms.

The evolutionary biologist James Mallet concludes that

there is no easy way to tell whether related geographic or temporal forms belong to the same or different species. Species gaps can be verified only locally and at a point of time. One is forced to admit that Darwin's insight is correct: any local reality or integrity of species is greatly reduced over large geographic ranges and time periods.

Aggregates of microspeciesedit

The species concept is further weakened by the existence of microspecies, groups of organisms, including many plants, with very little genetic variability, usually forming species aggregates. For example, the dandelion Taraxacum officinale and the blackberry Rubus fruticosus are aggregates with many microspecies—perhaps 400 in the case of the blackberry and over 200 in the dandelion, complicated by hybridisation, apomixis and polyploidy, making gene flow between populations difficult to determine, and their taxonomy debatable. Species complexes occur in insects such as Heliconius butterflies, vertebrates such as Hypsiboas treefrogs, and fungi such as the fly agaric.

Blackberries belong to any of hundreds of microspecies of the Rubus fruticosus species aggregate.

The butterfly genus Heliconius contains many similar species.

The Hypsiboas calcaratus–fasciatus species complex contains at least six species of treefrog.

Hybridisationedit

Natural hybridisation presents a challenge to the concept of a reproductively isolated species, as fertile hybrids permit gene flow between two populations. For example, the carrion crow Corvus corone and the hooded crow Corvus cornix appear and are classified as separate species, yet they hybridise freely where their geographical ranges overlap.

- Hybridisation of carrion and hooded crows permits gene flow between 'species'

Carrion crow

Hybrid with dark belly, dark gray nape

Hybrid with dark belly

Hooded crow

Ring speciesedit

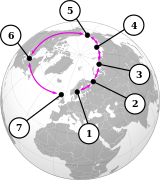

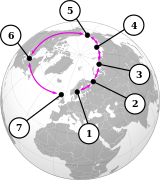

A ring species is a connected series of neighbouring populations, each of which can sexually interbreed with adjacent related populations, but for which there exist at least two "end" populations in the series, which are too distantly related to interbreed, though there is a potential gene flow between each "linked" population. Such non-breeding, though genetically connected, "end" populations may co-exist in the same region thus closing the ring. Ring species thus present a difficulty for any species concept that relies on reproductive isolation. However, ring species are at best rare. Proposed examples include the herring gull-lesser black-backed gull complex around the North pole, the Ensatina eschscholtzii group of 19 populations of salamanders in America, and the greenish warbler in Asia, but many so-called ring species have turned out to be the result of misclassification leading to questions on whether there really are any ring species.

Seven "species" of Larus gulls interbreed in a ring around the Arctic.

Opposite ends of the ring: a herring gull (Larus argentatus) (front) and a lesser black-backed gull (Larus fuscus) in Norway

A greenish warbler, Phylloscopus trochiloides

Presumed evolution of five "species" of greenish warblers around Himalayas

Comments

Post a Comment